Latest Updates

-

Dhurandhar 16 Days Collection | Dhurandhar Beats Jawan, Stree 2 | Dhurandhar 500cr | Dhurandhar Day 16 Collection | Dhurandhar Box Office Collection Day 17 Prediction (December 21, 2025) | Dhurandhar Third Weekend Collection Prediction | Dhurandhar Today Collection

Dhurandhar 16 Days Collection | Dhurandhar Beats Jawan, Stree 2 | Dhurandhar 500cr | Dhurandhar Day 16 Collection | Dhurandhar Box Office Collection Day 17 Prediction (December 21, 2025) | Dhurandhar Third Weekend Collection Prediction | Dhurandhar Today Collection -

How to Dress Well This Holiday Season Without Overthinking It

How to Dress Well This Holiday Season Without Overthinking It -

From Guava To Kiwi: Fruits to Have in Winters to Boost Your Immunity

From Guava To Kiwi: Fruits to Have in Winters to Boost Your Immunity -

David Guetta Returns to Mumbai After 8 Years, Lights Up Sunburn Festival 2025

David Guetta Returns to Mumbai After 8 Years, Lights Up Sunburn Festival 2025 -

How Homeopathic Remedies May Support Gut and Brain Health, Expert Explains

How Homeopathic Remedies May Support Gut and Brain Health, Expert Explains -

Why Viral Fevers Are Lasting Longer This Year: Expert Explains The Immunity Shift Post-COVID

Why Viral Fevers Are Lasting Longer This Year: Expert Explains The Immunity Shift Post-COVID -

Rekha’s Timeless Wedding Season Style: 5 Things to Pick From Her Latest Look

Rekha’s Timeless Wedding Season Style: 5 Things to Pick From Her Latest Look -

Gold Rate Today in India Flat, Silver Prices Jump to New High of Rs 2.14 Lakh: Check Latest Prices in Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Pune, Ahmedabad & Delhi

Gold Rate Today in India Flat, Silver Prices Jump to New High of Rs 2.14 Lakh: Check Latest Prices in Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Pune, Ahmedabad & Delhi -

Happy Birthday Tamannaah Bhatia: What The 'Baahubali' Star's ‘Milky Beauty’ Skincare Looks Like Off Screen

Happy Birthday Tamannaah Bhatia: What The 'Baahubali' Star's ‘Milky Beauty’ Skincare Looks Like Off Screen -

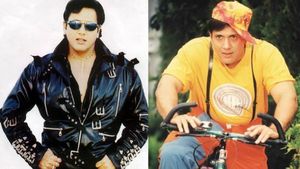

Govinda Birthday Special: Chi-Chi’s Bold And Unapologetic 90s Fashion Broke Every Style Rule

Govinda Birthday Special: Chi-Chi’s Bold And Unapologetic 90s Fashion Broke Every Style Rule

Commonsense About The Senses

Sunil,

the

municipal

clerk,

known

for

his

drinking

habit,

was

on

his

way

to

the

office.

'Hello,'

intercepted

his

colleague

on

the

way.

'What

happened

to

your

ear?'

he

asked

Sunil,

pointing

to

the

bandage

wrapped

around

Sunil's

right

ear.

'Oh, that is nothing,' he explained, 'yesterday, I had taken a little more than the usual, and when I came home, I found the phone ringing. And then, someone at home had switched on the iron box, and I, wanting to answer the call, mistakenly picked up…'

'But

what

about

the

left

ear?'

asked

the

curious

colleague.

'That

fool

of

a

man

called

up

again,'

regretted

Sunil.

Repeating

mistakes

is

nothing

new.

Most

of

us

not

only

commit

mistakes,

we

also

do

not

learn

from

them.

We

thus

keep

repeating

them

until,

perhaps,

we

learn

our

lessons.

Nowhere

is

this

more

true

than

in

understanding

the

nature

of

happiness.

Quest

for

Knowledge

The

quest

for

happiness

is

as

old

as

history.

But

like

Sunil,

we

keep

making

mistakes,

and

blame

the

world

for

our

unhappiness.

Though

this

search

for

happiness

is

basic

to

life

itself,

few

people

discover

lasting

happiness

in

life.

Hence,

although

everyone

becomes

happy

for

sometime

or

the

other,

no

one

seems

to

be

perennially

happy

in

life.

One

reason

for

this

is,

that

the

'reasons'

that

produce

happiness

are

themselves

not

lasting.

What

we

generally

call

as

happiness

is

caused

by

a

reason—success

in

examinations,

victory

in

a

football

match,

a

hike

in

salary,

acquisition

of

property

or

money,

admission

to

a

coveted

institution—we

seem

to

have

a

long

list

of

reasons

to

be

happy.

But the circumstances change; rules undergo alterations; situations shift; youth becomes old; rich grow poor, and the poor grow rich. Change after all is the inevitable nature of life. Success in examination does not bring happiness always. Although our favourite football team wins the match, a business loss casts a gloom over the mind and we cannot enjoy the victory. We are promoted but along with it comes the jealousy and politicking of those deprived of it, followed by retirement. Like the shifting landscape in a desert, life keeps changing. This is what most people discover—after much hard struggle and bitter experience—this changing nature of everything.

If this changing nature of life is a reality—which indeed it is—what should we do then? Stop seeking happiness? Stop working? Stop eating, and stop living? Far from it. Sri Krishna advises us in the Gita,1 'Having got into this impermanent world made up of shifting, changing reasons for happiness, seek immortality.' He does not ask us to stop seeking happiness, but learn to seek a permanent source of happiness (and assures that it is possible). Until we learn our lessons, we shall be taught this truth again and again.

One theme that is dear to all teachers of spirituality is asking the aspirants to seek permanent happiness, and stop seeking happiness in the pleasures of the senses. This, of course, amounts to saying, look for a source which is more lasting, and thus higher. We often hear them saying this in different ways: control your passions, do not run after the objects of senses, practise self-control, overcome your desires, and so on. Since sensory experience is what most of us know about life, these words of advice sound astonishing, and often unpleasant to most people. 'Why control the senses? Why not live as one wishes to live? What is wrong in running after sense pleasures?' And finally, 'What shall we gain by controlling them?'

Before answering these queries and objections, it would be of much help if we understand what is meant by senses. This is very essential, for, understanding the nature and working of something is the first step towards using it meaningfully.

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications