Latest Updates

-

International Human Solidarity Day 2025: History, Significance, and Why It Matters

International Human Solidarity Day 2025: History, Significance, and Why It Matters -

Purported Video of Muslim Mob Lynching & Hanging Hindu Youth In Bangladesh Shocks Internet

Purported Video of Muslim Mob Lynching & Hanging Hindu Youth In Bangladesh Shocks Internet -

A Hotel on Wheels: Bihar Rolls Out Its First Luxury Caravan Buses

A Hotel on Wheels: Bihar Rolls Out Its First Luxury Caravan Buses -

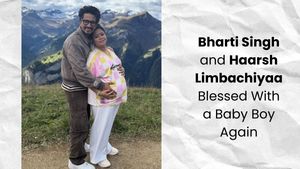

Bharti Singh-Haarsh Limbachiyaa Welcome Second Child, Gender: Couple Welcome Their Second Baby, Duo Overjoyed - Report | Bharti Singh Gives Birth To Second Baby Boy | Gender Of Bharti Singh Haarsh Limbachiyaa Second Baby

Bharti Singh-Haarsh Limbachiyaa Welcome Second Child, Gender: Couple Welcome Their Second Baby, Duo Overjoyed - Report | Bharti Singh Gives Birth To Second Baby Boy | Gender Of Bharti Singh Haarsh Limbachiyaa Second Baby -

Bharti Singh Welcomes Second Son: Joyous News for the Comedian and Her Family

Bharti Singh Welcomes Second Son: Joyous News for the Comedian and Her Family -

Gold & Silver Rates Today in India: 22K, 24K, 18K & MCX Prices Fall After Continuous Rally; Check Latest Gold Rates in Chennai, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad & Other Cities on 19 December

Gold & Silver Rates Today in India: 22K, 24K, 18K & MCX Prices Fall After Continuous Rally; Check Latest Gold Rates in Chennai, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad & Other Cities on 19 December -

Nick Jonas Dancing to Dhurandhar’s “Shararat” Song Goes Viral

Nick Jonas Dancing to Dhurandhar’s “Shararat” Song Goes Viral -

From Consciousness To Cosmos: Understanding Reality Through The Vedic Lens

From Consciousness To Cosmos: Understanding Reality Through The Vedic Lens -

The Sunscreen Confusion: Expert Explains How to Choose What Actually Works in Indian Weather

The Sunscreen Confusion: Expert Explains How to Choose What Actually Works in Indian Weather -

On Goa Liberation Day 2025, A Look At How Freedom Shaped Goa Into A Celebrity-Favourite Retreat

On Goa Liberation Day 2025, A Look At How Freedom Shaped Goa Into A Celebrity-Favourite Retreat

mexican nurses

CUETZALAN, Mexico, Nov 20 (Reuters) From cutting the umbilical chord to post-natal surgery, giving birth in the remote Sierra Norte Mountains of central Mexico used to be a dirty and dangerous experience.

''We had nothing, not even scissors,'' said Josefina Amable, a 56-year-old Nahua Indian, as she set out shoeless from a mountain hamlet to see a heavily pregnant patient. ''We used a machete cleaned with rum and needles for sewing clothes.'' Since before the Spanish conquest of Mexico, hardy midwives like Amable have trudged barefoot through the remote sub-tropical mountains, bringing babies into the world armed with bundles of herbs and centuries of hand-me-down wisdom.

Now, under a government pilot program mixing high-tech with sacred tradition, these midwives -- often the only people many women trust in one of Mexico's poorest regions -- are helping doctors keep mothers and babies alive, while picking up new tips from modern medicine.

Struggling to draw inhabitants of non Spanish-speaking areas lacking basic services into a health system many mistrusted, officials in the heavily indigenous central Mexican state of Puebla enlisted some unconventional help.

In five clinics attached to rural hospitals, medicine men, midwives and village osteopaths or 'bone-men' work alongside conventional surgeons, radiographers and obstetricians.

Stocked with curative herbs and equipped with altars where healers perform cleansing ceremonies, the clinics entice Indian patients into the hospitals, where conventional doctors can also detect and treat graver ills.

''We want to be a bridge between traditional and conventional medicine,'' said Margarita Alvarado, administrator of the clinic in the cobblestoned coffee-farming town of Cuetzalan, set up five years ago, the first under the program.

The Nahua midwives, who speak little Spanish and shun shoes, cut maternal and infant death rates by bringing mothers in for check-ups and convincing them to give birth in a hospital rather than at home, doctors say.

PAST MEETS PRESENT the clinic hummed with consonant-heavy Nahuatl one recent morning as pregnant women wearing embroidered Indian blouses waited in line.

In one room, 66-year-old midwife Michaela Perez muttered a prayer in Nahuatl, massaging the belly of a supine 28-year-old whose baby she had recently delivered.

Many mothers-to-be visit the clinic to treat ailments like 'fright' and 'evil-eye'-- afflictions they believe can be caused by evil spirits or spells.

''You can't explain 'fright' scientifically,'' said Alvarado.

''But I've seen women with it and here we cure it.'' A specially adapted delivery room has a metal frame women can grip to give birth in a traditional squatting stance.

But with the midwives standing by, expectant mothers who may never have even seen a computer are also unfazed by ultra-modern treatments that might otherwise scare them.

Leonor Vazquez, a tiny old woman in a billowing lace blouse, filed three young women one after the other into a gynecologist's surgery where they sheepishly watched their babies' hearts beating on a grainy ultrasound screen.

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications