Latest Updates

-

A Hotel on Wheels: Bihar Rolls Out Its First Luxury Caravan Buses

A Hotel on Wheels: Bihar Rolls Out Its First Luxury Caravan Buses -

Bharti Singh-Haarsh Limbachiyaa Welcome Second Child, Gender: Couple Welcome Their Second Baby, Duo Overjoyed - Report | Bharti Singh Gives Birth To Second Baby Boy | Gender Of Bharti Singh Haarsh Limbachiyaa Second Baby

Bharti Singh-Haarsh Limbachiyaa Welcome Second Child, Gender: Couple Welcome Their Second Baby, Duo Overjoyed - Report | Bharti Singh Gives Birth To Second Baby Boy | Gender Of Bharti Singh Haarsh Limbachiyaa Second Baby -

Bharti Singh Welcomes Second Son: Joyous News for the Comedian and Her Family

Bharti Singh Welcomes Second Son: Joyous News for the Comedian and Her Family -

Gold & Silver Rates Today in India: 22K, 24K, 18K & MCX Prices Fall After Continuous Rally; Check Latest Gold Rates in Chennai, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad & Other Cities on 19 December

Gold & Silver Rates Today in India: 22K, 24K, 18K & MCX Prices Fall After Continuous Rally; Check Latest Gold Rates in Chennai, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad & Other Cities on 19 December -

Nick Jonas Dancing to Dhurandhar’s “Shararat” Song Goes Viral

Nick Jonas Dancing to Dhurandhar’s “Shararat” Song Goes Viral -

From Consciousness To Cosmos: Understanding Reality Through The Vedic Lens

From Consciousness To Cosmos: Understanding Reality Through The Vedic Lens -

The Sunscreen Confusion: Expert Explains How to Choose What Actually Works in Indian Weather

The Sunscreen Confusion: Expert Explains How to Choose What Actually Works in Indian Weather -

On Goa Liberation Day 2025, A Look At How Freedom Shaped Goa Into A Celebrity-Favourite Retreat

On Goa Liberation Day 2025, A Look At How Freedom Shaped Goa Into A Celebrity-Favourite Retreat -

Daily Horoscope, Dec 19, 2025: Libra to Pisces; Astrological Prediction for all Zodiac Signs

Daily Horoscope, Dec 19, 2025: Libra to Pisces; Astrological Prediction for all Zodiac Signs -

Paush Amavasya 2025: Do These Most Powerful Rituals For Closure On The Final Amavasya Of The Year

Paush Amavasya 2025: Do These Most Powerful Rituals For Closure On The Final Amavasya Of The Year

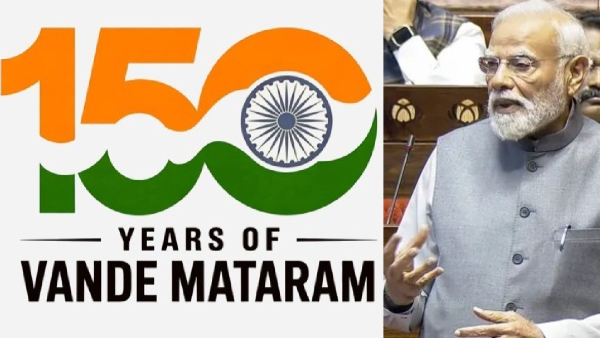

150 Years of Vande Mataram: Parliament Debates Missing Verses, Know Why Nehru Rejected It As National Anthem

On the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram, Parliament is holding a special session, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi currently addressing the Lok Sabha to open the debate.

Lawmakers are discussing the "missing verses" from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's original poem. The government is emphasising the importance of recognising the full composition, including the later, religiously rich stanzas, while the Opposition is expected to highlight that only the first two stanzas have traditionally been used, a decision made historically to ensure the song's inclusivity across communities.

As the session unfolds, the anniversary of Vande Mataram is not just a literary commemoration but also a moment to revisit questions of history, symbolism, and national identity.

The Original Poem And Why Some Stanzas Went Missing

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay first wrote Vande Mataram in the 1870s and later included it in his novel Anandamath. The complete poem consists of six stanzas, but only the first two were adopted for national use.

The remaining stanzas contain goddess imagery, powerful for many, but potentially exclusionary for a religiously diverse population. Leaders from the freedom movement, well aware of communal tensions, opted to promote the verses that celebrated the motherland without invoking specific deities.

Why Nehru Opposed Making Vande Mataram the National Anthem

When the Constituent Assembly was debating India's national symbols between 1947 and 1949, Jawaharlal Nehru played a key role in the decision not to select Vande Mataram as the national anthem.

There were three major reasons:

Religious Imagery: The later stanzas evoke goddess forms like Durga. Nehru believed a national anthem must be acceptable to every community, especially right after Partition.

Musical Practicality: Jana Gana Mana already had a fully developed musical structure by Tagore, suitable for military and ceremonial use. Vande Mataram did not have one universally accepted tune.

Honour Without Compulsion: Nehru insisted that Vande Mataram should continue to be honoured for its role in the freedom struggle, but not made mandatory as an anthem.

This led to the historic compromise recorded in the Constituent Assembly on 24 January 1950:

Jana Gana Mana became the National Anthem, Vande Mataram was given equal cultural honour as the National Song.

Lesser-Known Facts About Vande Mataram

It Was First Published On Akshaya Navami In 1875

Before finding a place in Anandamath, Vande Mataram first appeared in 1875 in Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's literary magazine Bangadarshan. What makes this moment particularly meaningful is the date of publication, it was released on Akshaya Navami, an auspicious day in the Hindu lunar calendar associated with new beginnings, prosperity, and enduring success.

The symbolism is striking in hindsight: a song that would later become a rallying cry for India's freedom was first introduced on a day believed to ensure that what begins will grow and endure.

The Popular Tune Was Composed Later By Rabindranath Tagore

The version most people know today was set to music by Tagore, who sang it publicly in 1896 at a Congress session. Bankim never composed an official tune.

British Rule Tried To Restrict Its Public Singing

During the Swadeshi movement, colonial authorities viewed the song as a threat and discouraged its public chanting, especially during protests and processions.

It Became A Rallying Cry In Freedom Movements

From the 1900s to the 1940s, the phrase "Vande Mataram" was shouted during marches, strikes, and underground resistance, functioning almost like a revolutionary password.

The Constituent Assembly Formally Debated Its Status

On 24 January 1950, the Assembly officially recognised Vande Mataram as the National Song, granting it a unique symbolic status alongside the National Anthem.

Many State Legislatures Still Begin Sessions With It

Several state assemblies traditionally start their sittings with Vande Mataram, maintaining a long-standing political and cultural ritual.

The Song Has Been Translated Many Times

From English to Tamil, Urdu to Hindi, more than a dozen translations exist, many produced in secret during the colonial era to avoid censorship.

The Controversy Is Not New

Concerns about inclusivity versus heritage were debated even in the 1930s by nationalist leaders. The present-day argument is essentially a continuation of an old dilemma.

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications